Happy Tuesday, bibliophiles!

Confession time: I was not a fan of Kemi Ashing-Giwa’s debut, The Splinter in the Sky. I didn’t think I would read any of her other books. But my hunger for sci-fi knows no bounds, and when I saw this, I was intrigued enough by the premise to give her writing a second shot. Thankfully, the gamble paid off—The King Must Die was an unexpected delight, full of rebellion, blood, and the friendships that somehow spring up from those other two things.

Enjoy this week’s review!

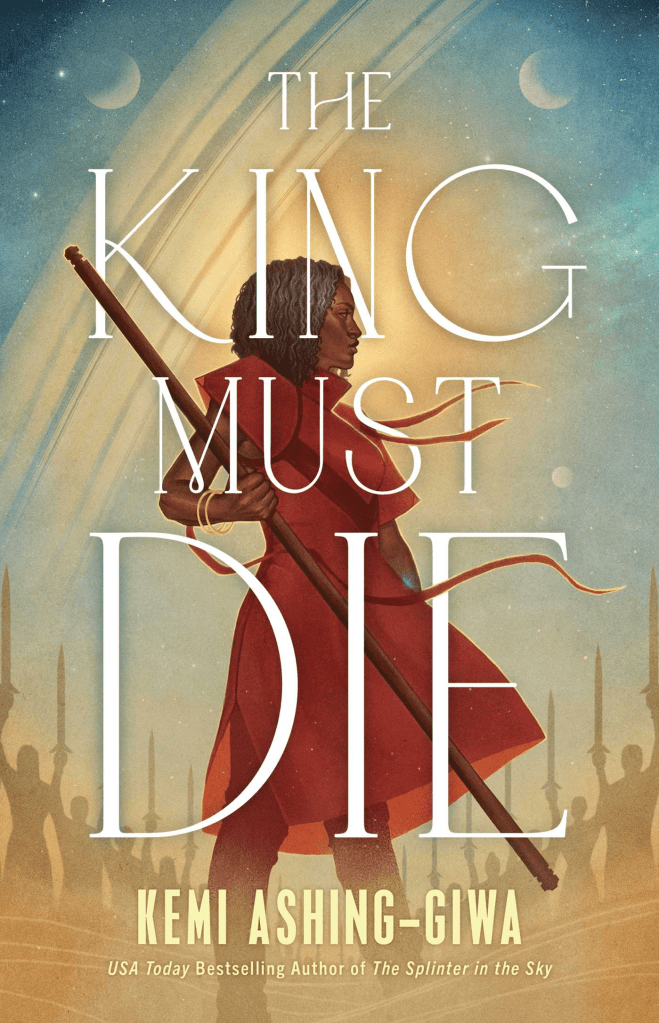

The King Must Die – Kemi Ashing-Giwa

Newearth was once humanity’s last hope, a planet terraformed by incomprehensible, alien overlords. Now, it’s on the verge of destruction, with dwindling resources divided unfairly amongst the struggling poor and the Sovereign that rules over them. What’s more, the Sovereign has the power of the omnipotent, alien Executors on their side, willing to do their divine bidding at a moment’s notice, leaving a path of destruction in their wake. Fen, the daughter of anti-imperialist rebels, is on the run after the assassination of her fathers. With a target on her back, she flees for a neighboring rebel faction. But when Alekhai, the ruthless heir to the Sovereign, stumbles directly into the plans of the rebellion, Fen is faced with a brutal choice: join forces with him, or let the rebellion fall prey to the Sovereign.

TW/CW: murder, loss of loved ones, gore, blood, violence, descriptions of injuries, torture

I almost passed on this novel when I saw that it was by the same author as The Splinter in the Sky. But sometimes, every once in a while, it’s worth it to give an author another chance; if not for second chances, I wouldn’t have loved Grace Curtis’s Floating Hotel, for instance! I’m glad I took the chance with Kemi Ashing-Giwa, because The King Must Die was an action-packed, adrenaline-filled story of rebellion and intrigue.

My issue with The Splinter in the Sky was that the story did not feel original. A recurring thought I had while reading it was that it had poorly copied A Memory Called Empire‘s homework—there wasn’t enough about the story that was original. I can excuse some of it, since this was her debut novel, but debut novels can have a story that doesn’t border on being a rip-off. That being said, I do remember liking some of Ashing-Giwa’s prose. Thankfully, she’s worked on both of those fronts, creating an original story to go with said prose, and the prose itself has been leveled up significantly! Ashing-Giwa had such a vibrant way of describing the imagined world of Newearth and the many people within it, so much so that I could easily see myself walking through its war-torn jungles. Her dialogue is snappy without being corny, and her metaphors added a poetic flair to an often bloody and dreary landscape. The King Must Die is a marked improvement from Ashing-Giwa’s debut, fleshing out what I felt lacked in her writing on the first time around.

Whenever I say that an adult novel is a good transitory novel between YA and Adult age groups, it always seems backhanded. I guess that’s because literary circles still turn their noses up at YA for the most part. Listen—even though I’ve aged out of the target audience, I read a fair amount of YA (although adult novels have eclipsed them), I write YA, and I have a deep respect for it as an age group (it’s not a genre!). There’s a difference between YA (novels that genuinely portray the complex emotions of teenagers and their circumstances) and YA (tropey slop banking on the latest fanfiction/TV trends). And I think there’s something about The King Must Die that felt like it could be an excellent book to introduce older teens to more adult genre fiction. Sure, the kill count and amount of blood in general is very much adult, but Ashing-Giwa hits that balance between the political intrigue that’s more present in Adult novels with the character drama that I associate more with YA. It has the fast pace that I associate with some of my favorite YA sci-fi romps that I ate up in high school, but with a level of maturity that would have been lost on me at that time. It’s difficult to balance this kind of complicated worldbuilding and politics while also having this character drama, but The King Must Die had both in spades.

The main part that felt YA (affectionate) to me was the character dynamics. The dynamic between Fen and Alekhai is a classic YA setup; she’s a runaway rebel, and he’s the heir to the empire she wants to destroy. Will sparks fly? …no, evidently, but they did make for some seriously compelling character dynamics. I appreciated that, although there were multiple opportunities for Fen to be paired off with any number of characters, all of them were platonic, and they still gave me that juicy, delectable drama that’s usually only reserved for romances. Fen had such excellent chemistry with Mettan, Sinjara, and the other rebels, but what stood out the most was her relationship with Alekhai. I love a good redemption story for a villain, but it’s even more impressive given how much that Ashing-Giwa establishes about him that honestly…shouldn’t be that redeemable. But his development over the course of the story culminated in something so emotional, and the slow cracking of his shell from a ruthless, indestructible royal to someone who only wanted love in return was incredibly poignant.

The King Must Die is still sci-fi for sure, but I’d place it somewhere in the nebulous category of space fantasy. There are some elements that solidly ground it in science fiction: the alien Makers and their terraformed planet, for one, but also some of the technology. However, much of the action that we see on the ground was very fantasy, what with battles waged with intricate swords and quarterstaffs. I loved the strange, often horrifying beasts that we encounter throughout, though I would’ve liked explanations about how they fit into the ecosystems; we get a lot of tidbits of creatures that supposedly went extinct centuries ago, but are showing up for…reasons, and are never brought up again. As a whole, there were a handful of holes in the parts of the worldbuilding that didn’t relate to a) the politics or b) the terraformed Newearth, but for the most part, the world of The King Must Die was a compelling one without a doubt.

In general, I liked the ending and the epilogue; on a more technical level, Ashing-Giwa is excellent at writing battle scenes that really pump up your adrenaline. Some of the imagery, as well as Askrynath’s dialogue, reminded me of the final battle in the throne room in Hellboy II: The Golden Army, which, if you know me well, is a compliment of the highest order. Conceptually, I like how the ending and epilogue resolved—through selflessness and collective community work, the empire was dismantled and a more fair system was set up on Newearth. However, it felt wrapped up far too neatly. An empire that size—especially one with the backing of incomprehensibly all-powerful aliens—doesn’t crumble in a day. I wanted to see more of the messiness of rebuilding a new world in the ashes of the old one—the transition just felt too clean to be realistic. To be fair, The King Must Die is already pushing 500 pages, so I get it if that didn’t make the final cut. Nonetheless, it was a satisfying ending—just too satisfying for my liking, and for the tone of the story itself.

All in all, a sci-fi adventure that balanced genuine political critique with fast-paced action and dramatic, snappy dialogue—it’s rare to find a book that succeeds with both. 4 stars!

The King Must Die is a standalone, but Kemi Ashing-Giwa is also the author of The Splinter in the Sky and the novella This World Is Not Yours.

Today’s song:

That’s it for this week’s Book Review Tuesday! Have a wonderful rest of your day, and take care of yourselves!