Happy Tuesday, bibliophiles!

I’ve read a lot of great books this month, but a lot of the ones I’ve read recently are sequels to books that I haven’t reviewed, so it feels weird to review a book 2 or 3 when I haven’t even review book 1. Hence why there have been more negative reviews this month. However, I do feel like I have to get my feelings about Every Variable of Us off my chest, because it promised something so positive, but crashed in burned in so many ways. It was a sore disappointment for sure.

Enjoy this week’s review!

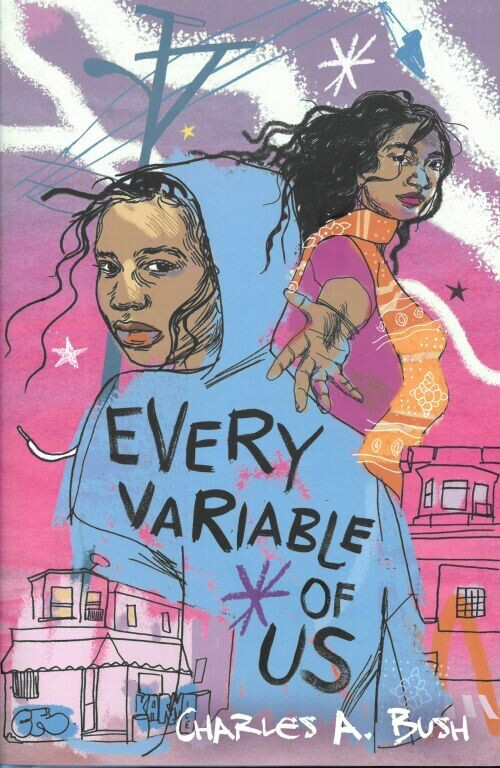

Every Variable of Us – Charles A. Bush

Alexis Duncan loves basketball—and she’s counting on it to get her the scholarship she needs to escape her impoverished neighborhood and turbulent home life. But when she’s injured in a shooting and can no longer play basketball, her dreams are crushed. With no other option, she turns to Aamani, the new student in her school. Aamani encourages Alexis to join their school’s STEM team to get the scholarship she needs. Alexis is skeptical—she knows nothing about the sport, and she’s reluctant to fit in with the nerdier crowd. But as her skills—and her confusing crush on Aamani—develop, Alexis realizes that there may be more to her than meets the eye.

TW/CW: racism, gun violence, homophobia, Islamophobia, xenophobia, ableism (internalized/external), drug abuse/addiction themes, mentions of child abuse

I’m a little ashamed to be giving this novel such a negative review, but I firmly believe that negative reviews have their place. This novel was clearly a labor of love for Bush, being a debut novel about a queer, Black, and disabled girl, a story that’s exceedingly difficult to get out there in this climate. There’s probably some kids out there who think that this is just the book for them. Without a doubt, Every Variable of Us is an important book to have out there. But I think there’s a lot of valid criticism to be had for this novel, and it’s important to note that a book being diverse doesn’t absolve flaws in its writing…of which this novel had many.

In theory, I think Alexis is a great character to have for a YA audience; there’s this expectation in the genre that even your characters can’t be flawed in terms of their worldview, because that might be “problematic.” It’s good for teens to see a character that starts off narrow-minded and comes out the other side more tolerant or understanding. I tried to roll with Alexis’s inner monologue with that in mind. There’s a lot that you have to put up with—in the beginning of the book, Alexis is…practically everything-phobic: Islamophobic, racist towards other minorities, fatphobic, homophobic, and ableist. There’s a clear setup for her to learn from her mistakes and be more understanding of other people’s cultures, and in turn, accept her own status as a disabled, bisexual person. However, there doesn’t end up being much development on her part, when both the novel and the marketing want us to believe that she undergoes this dramatic arc and becomes a whole new person. Alexis becomes more tolerant towards queerness and Aamani’s Indian heritage and traditions, but save for that (and her success in becoming an asset to the STEM team and getting a scholarship), her arc is practically a straight line. Her lack of self-reflection wouldn’t have been a problem if Bush wanted the reader so badly to think that she’d magically changed into a better person, when in reality, she was in a very similar place to where she was at the beginning of the novel. I’m all for flawed characters, but don’t tell me that a character’s had this monumental shift in her worldview when she really hasn’t.

Which brings me to the complicated issue of the diversity of this book. I really appreciate that Bush put a lot of effort into making Every Variable of Us have a diverse cast. However, a lot of the diverse characters ended up feeling like props to reinforce lessons for Alexis about being tolerant about other marginalized people. To be fair, Aamani had more development than the rest, but there were moments when she was clearly only there to teach Alexis about Indian people and Hindu traditions, as well as queerness. It was more blatantly evident in characters like Matthew; I appreciated the note at the beginning where Bush acknowledged that he’s not autistic and wanted to represent autism as respectfully as possible. I can’t speak to the autism rep specifically, but as a neurodivergent person, I found Matthew to be decently represented. That being said, it very much felt like he was there just so that he could challenge Alexis’s ableist worldview. At a certain point, I could see the checklist in Bush’s head: “oh, wait! Maybe we can add an Asian character here, jot that down!” Diversity can only be successful when its intent is to provide representation of minorities, but also minorities as people, not teaching moments for the main character; otherwise, it becomes disingenuous. Every Variable of Us unfortunately fell straight into this trap.

I’ve talked about this with several YA books, but there’s a very vocal camp in the YA world that’s staunchly against pop culture references in the story. I’ve never really understood the argument—why not have your characters engage with media that current teenagers like and/or that you liked as a teenager? Why not have something that a teenager can relate to or be introduced to because of this book? However, there is very much a wrong way to do it, and that’s to cram every possible reference into the narrative for no reason. Dear Wendy is another example where that approach nosedived (too many references, not enough actual story), but it pains me to say that Every Variable of Us is also a masterclass on how not to write pop culture references into the narrative. Every other sentence had a reference. Even when I was Alexis’s age, and deeply, deeply nerdy (especially about some of the same things that Aamani is passionate about, namely Marvel comics), my inner and outer monologue didn’t contain an Avengers reference every 10 seconds. It got to such a ridiculous point—nobody, not even nerdy people, talks like that at all. As a result, almost all of the characters ceased to become real to me. People just do not speak like that. It’s like Bush was trying to relate to every possible teenager by thinking of every possible thing that a teenager could like, and then translating it into dialogue, making it exceedingly hammy.

That issue of trying to relate to every possible teenager felt like the core of my issues with Every Variable of Us. It’s an issue that I often see in a lot of debut novels: authors want to cram every possible thing that they’re passionate about into a single novel; at best, it’s a labor of love, and at worst, it’s quite bloated. This novel suffered from this without a doubt. He just tried to tackle far too many issues, and as a result, the analysis of them was often surface-level. Bush talks about gang violence, abuse, having a parent with an addiction, homelessness, suddenly developing a disability, religious bigotry, and queerness all in one novel. While it’s admirable to write about this much (and there are of course people who live in these circumstances), Bush clearly didn’t have the page time to do justice to all of them without only giving an underdeveloped take on all but maybe…two or three of these issues. I do appreciate the handful of moments where the exploration of these topics actually did land; the moment at the end with Alexis’s mother was one of the only parts of the book that was emotionally impactful to me. But for the most part, this was just way too much for a single debut novel to be doing. In an attempt to try and address every issue that he seems to be outspoken about, Bush ends up hardly addressing them at all.

If there’s a lesson to be learned here, it’s that you can’t please everybody with a single novel, whether it’s the audience you’re appealing to or the groups that you’re trying to represent. Charles A. Bush just seemed too concerned with trying to make every possible reader in every parallel universe happy, which stretched the narrative thin. I get that there’s an insurmountable amount of pressure with a debut novel, but you do not need to please everybody! It’s okay! Breathe!

All in all, a debut novel that tried too hard to do too much, and ended up spiraling into a mess as a result. 1.75 stars.

Every Variable of Us is a standalone, and Charles A. Bush’s debut novel.

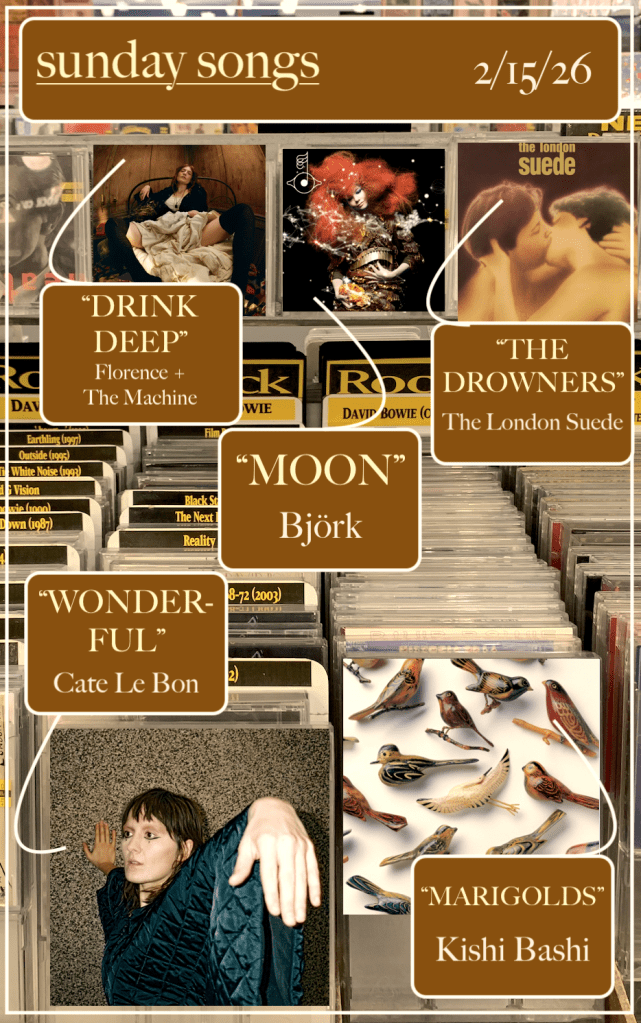

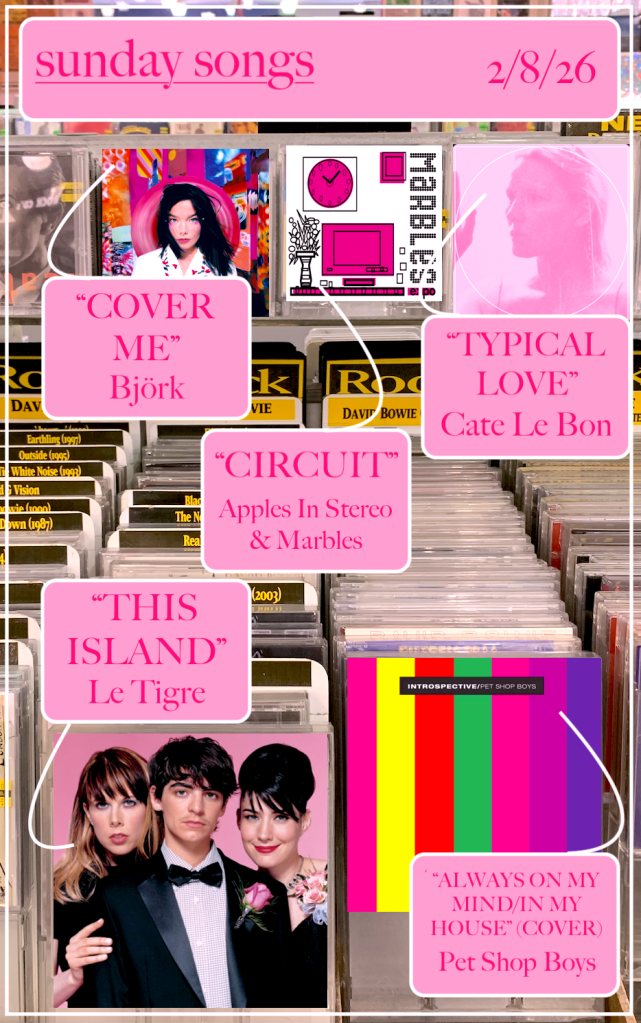

Today’s song:

That’s it for this week’s Book Review Tuesday! Have a wonderful rest of your day, and take care of yourselves!