Happy Tuesday, bibliophiles!

QUICK ANNOUNCEMENT: because I’m trying to divorce myself from Amazon as much as I can, I’m finally moving over from Goodreads to The Storygraph. From now on, my reviews will be available there @thebookishmutant.

I started the Sing Me to Sleep duology last year, and now that book 2 is out, I figured I would pick it up for Black History Month, but also so I could finally get some resolution! And I sure got a resolution…one that wasn’t as enjoyable as the first book, but nonetheless a twisty, romantic ending to a fantasy duology that balanced fun and social commentary.

Now, tread lightly! This review may contain spoilers for book one, Sing Me to Sleep. For my review of Sing Me to Sleep, click here!

Enjoy this week’s review!

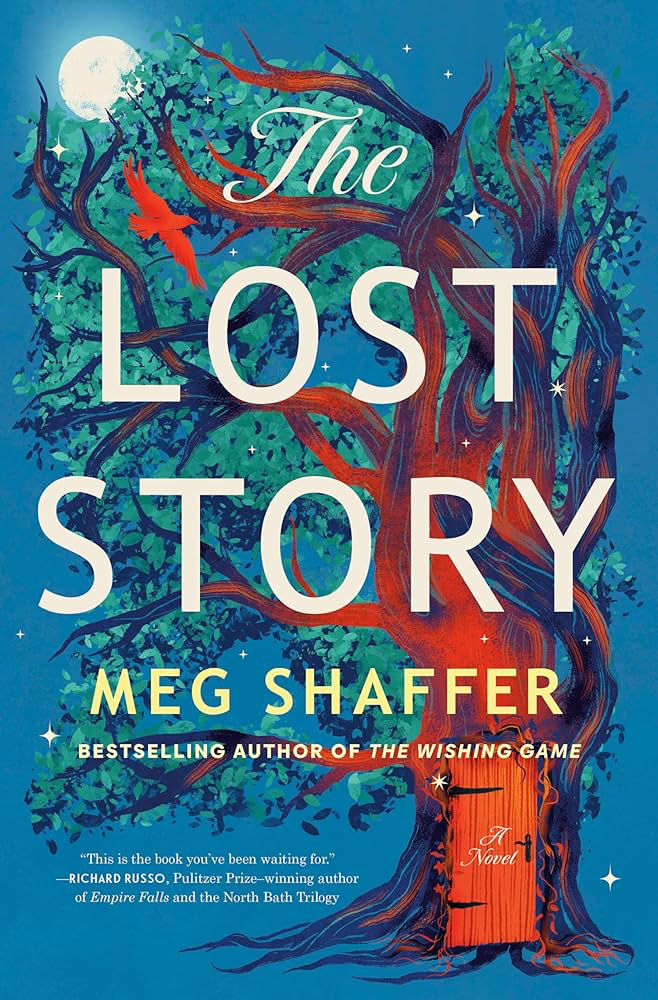

Drown Me with Dreams (Sing Me to Sleep, #2) – Gabi Burton

Saoirse is on the run. Now that her siren identity has been exposed, she must flee to the other side of the wall that divides Keirdre from the rest of the world. Taking sanctuary with the budding Resistance, Saoirse discovers a world full of different species that Keirdre drove out of its kingdom, all waiting for the day that they can take back what is rightfully theirs. But tensions are brewing, and war is imminent. On the other side of the wall, King Hayes, her secret love, awaits, but do his loyalties remain with Saoirse? And will Saoirse be able to fend off the rising tides of war?

TW/CW (from Gabi Burton): murder, graphic violence, discrimination/segregation (fantasy), genocide themes, blood, descriptions of injury, imprisonment

You would think that a book that’s over 400 pages would have plenty of time to work out all of the wrinkles in the plot and the worldbuilding…apparently not. In a perfect world, Drown Me with Dreams would be a great second book in a trilogy, but in this world, it was a duology concluder that tried to do far too much. That doesn’t mean that it was bad by any stretch of the imagination, but it was certainly a step below Sing Me to Sleep.

Oops. I end up stumbling into books with startling relevance to the current climate, and oh my god, am I sick of using that phrase. But. Drown Me with Dreams does an excellent job of expanding on its themes of resistance, racism, and misinformation! Saoirse has now figured out that there’s a wide world beyond the walls of Keirdre that has been obscured by the racist regime in her home kingdom; now that she knows the truth, she’s exposed to a myriad of perspectives and has to do the work herself to deconstruct the lies she’s been fed all of her life. She meets dozens of new mythical species that have been respectively discriminated against by Keirdre, and finds out firsthand how many falsehoods that the ruling powers have upheld for decades. The simultaneous revelations and discomfort of Saoirse discovering the truth is such a wonderful thing for a YA fantasy book like this to explore—in the end, it’s up to us, in our varying experiences in the real world, to discover the truth about how our governments can shape (and mis-shape) the narratives we grow up on. I also love the themes of solidarity present—fantasy or not, I love that the kind of feminism that Drown Me with Dreams champions is the kind that holds celebrating individual experience and solidarity under shared oppressions in equal regard. It’s the kind of unity that I believe will push feminism forward, and it made for a powerful statement in Drown Me with Dreams.

Even though Saoirse and King Hayes were kept apart for the first half of the novel, Drown Me with Dreams had a great resolution to their romance! Was it classic, YA fantasy romance cheese? Yes. Was it good cheese? Absolutely. To paraphrase one of my high school English teachers, there’s a difference between gourmet cheese and “American cheese-food.” I’ve been a YA reader for quite some time now, and there’s a difference between cringeworthy cheese and high-quality cheese. Drown Me with Dreams falls into the latter category, 100%. There’s angsty angry-kissing aplenty, but it’s written believably. If anyone is looking to do slow-burn, enemies-to-lovers romance right, look no further. Saoirse and Hayes weren’t just given enough time to have their romance develop—the stakes of their forbidden love were built up for the whole series, and their chemistry together made for some high quality smoldering. It’s not trying to be enemies-to-lovers in the way that most BookTok fantasy books try and fail to do—Burton’s given us a well-developed romance you can root for, and it made Drown Me with Dreams a standout read in that department.

In my review for Sing Me to Sleep, I mentioned that the book’s main flaw was that it was juggling far too many characters. In that same review, I commended Burton’s ability to craft a rich, layered fantasy world. Both of those aspects collided in Drown Me with Dreams with disappointing results. In Drown Me with Dreams, we finally see the world beyond Keirdre, and it’s full of all of the creatures that Keirdre drove out—dryads, goblins, sprites, you name it. On the surface, I was so excited to see this aspect of the world, but two main issues arose. The first was that we were introduced to a truckload of characters, almost 80% of which had barely anything memorable about them other than the fact that they were from a “new” species. Some of them were slightly consequential, but only just. I had so much trouble keeping track of all of them, which definitely muddied my reading experience. The second problem was that all of this worldbuilding was crammed into a single book—with a kingdom and world this expansive, it needed at least another book to develop fully, which hindered how fleshed out the world ended up being, after all of these promises of it being fascinating and new. (Also, I get the point about racist narratives being made with the goblins, but…what was the reason for making goblins into glorified elves? Why did they need to be conventionally attractive?)

Which brings me to my second major gripe: this series should not have been a duology. Not only are we introduced to a staggering amount of worldbuilding that only amounts to a single book, the same goes for the plot. A full resistance movement, the tensions within said resistance movement, the looming threat of war from multiple sides, and the fallout from said monumental war are crammed into 424 pages…should be enough, right? Most of what I described only happens in the last 2/3rds of the book, and nothing gets nearly the attention it deserves. We get dragged along with a pointless red herring of a love triangle (only for Saoirse to end up with her main romantic interest and for the other guy to just DIE GRUESOMELY? I didn’t really care about the guy, but pour one out for Carrik), and all of the interpersonal conflict rarely lasts, only providing detours on what should’ve been a rich plot on its own. As with the worldbuilding. Drown Me with Dreams should have had at least one more book to expand on everything. It’s a case of Burton biting off far more than she could chew, to unfulfilling results.

All in all, a duology-concluder that didn’t deliver on its epic worldbuilding promises and rushed its climax to a dizzying degree, but delivered on its past themes and promised romance. 3.5 stars!

Drown Me with Dreams is the second and final book in the Sing Me to Sleep duology, which begins with Sing Me to Sleep.

Today’s song:

That’s it for this week’s Book Review Tuesday! Have a wonderful rest of your day, and take care of yourselves!